The Construction of Mount Ievers - 1736

A Dreamlike House

In 1736, Colonel Henry Ievers built Mount Ievers on the site of the old tower house at Ballyarrilla. The new house has been variously described as Pre-Palladian, Queen Anne and early Georgian.

The Hon. Desmond Guinness is closest to the mark when he described it in 1975 as ‘an example of the time-lag in architectural styles to be found in the remoter parts of the country.’ The house reminded him of ‘a forlorn doll’s house’, an impression heightened by ‘a curious architectural deice’ whereby ‘at each of the stone bands or [cut-stone] string-courses that surround the house it become narrower by some nine inches.’

A few years later, Mark Bence Jones hailed it as ‘the most perfect and also probably the earliest of the tall Irish Houses’, possessed of ‘that dreamlike, melancholy air which all the best tall 18th century Irish houses have.

The Rothery Architects

The original architect of Mount Ievers was John Rothery, scion of a family highly regarded for their skills in architecture and stonemasonry in Munster. In 1733, he designed and built the Market House in Sixmilebridge, along the south bank of the river.

It seems likely that John was either a son or brother of a Joseph Rotherey [sic] who was recorded as living beside Castletown House in County Kildare at the time of its building between 1722 and 1729. Indeed, it is likely that the Rotherys actually oversaw the work at Castletown as its Italian architect Alessandro Galilei is known to have left Ireland before building commenced. In this regard, it is notable that the original interior layout of Castletown owed much to recently published plans of English houses such as Chevening in Kent, with a central hall and saloon surrounded by four apartments on the ground floor and a gallery flanked by apartments on the piano nobile level. Indeed, Castletown shares a number of features with Mount Ievers including the two huge chimney stacks, the plain facade and the corner fireplaces.

The Design

Mount Ievers is among the earliest and grandest of the tall Irish country houses, and was almost certainly inspired by the original 1679 drawings for Chevening, the old Lennard home in Kent which was sold to the Earl of Stanhope in 1717. The fact that Sir Sampson Eure’s mother was a Lennard of Chevening has given rise to the theory that Henry Ivers, grandfather of the Colonel Henry Ievers who built Mount Ievers, was a close kinsman of Sir Sampson.

It is also to be noted that Henry Ivers was employed by Lord Clare whose wife was a granddaughter of the Baron Dacre who built Chevening. There is certainly something here but precisely what still eludes us.

The Exterior

The result was a three-story, seven bay house with two fronts, the south elevation built of red brick over a high basement, the rear and side facades of rendered, cut limestone ashlar of a silvery hue. As well as the string-courses, there are eaves courses which run, along with a moulded frieze, under the hipped slate roof.

As the Irish Georgian Society notes: ‘The basement windows have segmental arched openings while those of the upper floors are square-headed with timber sash windows and limestone sills. The south entrance possesses timber-panelled doors between console brackets and under an entablature. A beautiful set of limestone steps leads to the piano nobile (the principal floor of the house).’ Desmond Guinness further pointed out that ‘the sash windows are of the earliest kind, with heavy glazing bars and four panes across instead of the three generally found.’

The Pease Family & The Dutch bricks

The pink-red brick used on the southern elevation of Mount Ievers was transported by ship from the Netherlands as ballast from Holland in exchange for oil squeezed out of rape-seed at the nearby Ballintlea oil mill on the River O’Garney.

At this time, the mill was almost certainly owned by George Pease (1683-1743). George was born in Amsterdam to which city his father Robert Pease (1643-1720), a once influential citizen of Hull in Yorkshire, had emigrated in about 1668, holding strong objections to the Restoration settlement. Giles Vandeleur, a Dutchman, operated the rape seed oil mill in Sixmilebridge in 1675. The Pease family seem to have acquired this mill, along with a linseed exporting business in Limerick. Under a scheme to introduce settlers in the area, George Pease brought in Dutch artisans and rebuilt the mills in 1696.

The Oak & Slates

The Galway town of Portumna, some 60m miles north-west of Mount Ievers, takes its name from the Irish ‘Port Omna’, meaning 'the landing place of the oak'. It is certainly an apt name from Mount Ievers perspective because thirty four tons of oak used in the construction of the houses’ hipped roof came from the Earl of Clanricarde’s woods at Portumna. The timber was transported south by boat across the waters of Lough Derg to Kilalloe, from where it was carted a further 30km by road.

The slates that adorn the roof of Mount Ievers were transported by road some 15km from the Broadford quarries amid the Slieve Bernagh hills. In 1833, the Broadford slates were regarded by a writer for Encyclopaedia Britannica as ‘nearly equal to the finest procured in Wales’. Henry Ievers acquired the slate at a cost of nine shillings and sixpence (47 ½ p) per thousand.

Ceilings & Walls

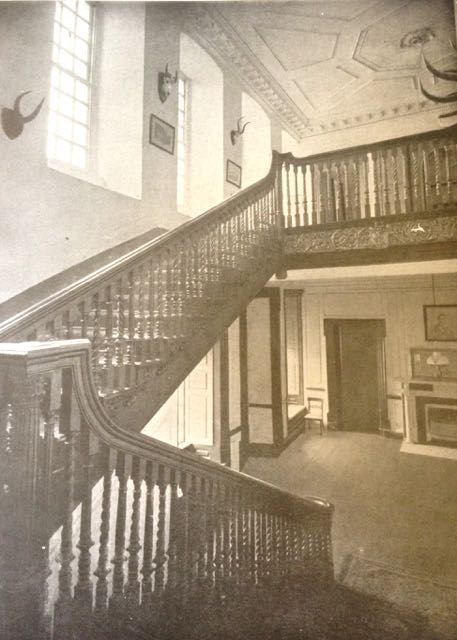

One of the most prominent features of the house are the brick-vaulted ceilings which run over all the ground floor rooms. Eyre Hebert Ievers pointed out that these vaulted ceilings provided were secure from the three upper floors. ‘A single, small thick door with a hole for a musket shut off the narrow stairs giving the only access inside from the ground floor’, he wrote. ‘Both first floor entrance doors and thick, hung on enormous hinges, are furnished with massive locks, and there are slots in the walls at the sides to take a 6 inch by 4 inch beam across the back’. In 1937, The Irish Times noted that ‘the original brass locks are on all the doors on the first floor, and a number of the old window seats remain.’ The ceilings and cornices in the hall, staircase and upper hall are paneled in pre-Georgian style. A stone fireplace dated 1648 was salvaged from the nearby castle and re-erected in the hall of the house where it still stands. The walls are often four to five feet thick and, in several rooms, they are panelled in plaster, as opposed to wood.

The Art

In the drawing room there is a beautiful fresco built into the wall which gives a panoramic view of the house, demesne and neighbourhood from about 1740. In the background of the painting one can see Bunratty Castle and the River Shannon beyond.

The Grounds

At the same time as the house was designed, a garden was formally laid out with rectangular fish-ponds. The panoramic Mount Ievers fresco of 1740 includes a walled yard on the west side of the house, as well as an obelisk, a Fish House, an Ice House and a Pigeon House. The courtyard boasts sentry boxes either side of the entrance gate.

The Labour

We are exceptionally fortunate that a complete set of the original building accounts has survived. [Where are these now?]. These provide vital details about both the labour costs and the source of the building materials, alluded to above. For instance, an entry for 11th September 1736 refers to the price of hiring ‘11 masons’ (£2 15 for one week) and ‘48 labourers’ (£1 for one week), showing that masons received five shillings a week for their work, while labourers earned a whopping five pence for the same hours. As Eyre H Ievers has noted in the Ievers File, the workers also received food, shoes and serge (the fabric), as well as firewood. Some of the tradesmen and senior staff would also probably have been housed.

The stonemasons and cutters were responsible for creating the handsome cut stone Georgian style south face out of grey limestone. According to The Archaeological journal, Volume 153, two cut-stone street names in Sixmilebridge are dated 1730. When Dr. Pococke visited in 1752, he also remarked on a ‘new’ parish church at Kilfinaghty, dedicated to St. Finaghta.[xi] As such, there must have been no shortage of experienced stonemasons in the area by the time Henry Ievers had completed his ambitious construction project.

With so much of the work relying on local labour and materials, the total cost of the house was £1,478 7s. 9d., a comparatively small amount by the standards of the time. According to the National Archives (UK) online currency converter, that would have the same spending worth of £127,570 in 2005. That said, by the same gauge, Henry Ievers was able to employ 48 labourers for a week for the grand total of £86.29. The cheapness of the Irish labour force in the 1730s becomes ever more evident from these weekly accounts for Mount Ievers.

Masons before [John] Rothery’s death: £81 19 2

Since his death to 23rd Nov 1737: £71 17 10

£153 17 0

Carpenters before his death: £79 8 1

Since his death to 23rd Nov: £35 9 8½

£114 17 9½

Stonecutters to the death of Mr Rothery: £180 1 5½

From the death to the new agreement: £27 17 10

From the new agreement to 23rd Nov 1737

£113 7 4

________

£321 6 7½

Entire cost of the whole building to Rothery’s death: £1053 9 8

From that to the new agreement: £311 10 9

From the new agreement to 23rd Nov 1737: £113 7 4

____________

£1,478 7 9

Besides two horses I gave Rothery, value £15 0 0

3,600 laths £1 16 0

Iron Riddle & Sledge 0 10 10

North view of Mount Ievers, The Pink-Brick from Holland is extremely attractive on a Summer's afternoon.

An old photo of the impressive Georgian staircase at Mount Ievers.

The 1648 Fireplace which was salvaged from the old Tower house that stood on Mount Ievers site before construction.

The top landing c. late 1940’s. The propeller was from Norman Lancelot Ievers stint as a pilot in the RAF and Battle of Britain. Notice the original timber floor from the 1730’s.

The ceiling of the 1st floor landing at Mount Ievers.